PPC120 | TECHNICAL

Niall Gallagher, BPCA Technical Manager, provides an overview of several insect species that, although often distressing, are not classified as public health pests.

Arthropods (or bugs, if you believe the marketing department here) come in many forms. We are all familiar with our traditional public health insects, such as cockroaches and bed bugs, but sometimes we come across ones that throw us a curveball in our line of work.

As pest professionals, we are often more than happy to roll up our sleeves and help reach a positive solution. But which bugs do we have limited scope to address?

From the invisible itch of dust mites to the unmistakable irritation of lice, a variety of tiny arthropods live in close association with humans. While most are more nuisance than danger, some can cause significant health issues, especially among vulnerable populations.

We've all been in situations where we've been asked to identify something that isn't a public health pest, or asked to give medical advice that is outside our scope of expertise. This article gives you an overview of a couple of usual suspects, tips on how you can ID them and where you can signpost people to for help.

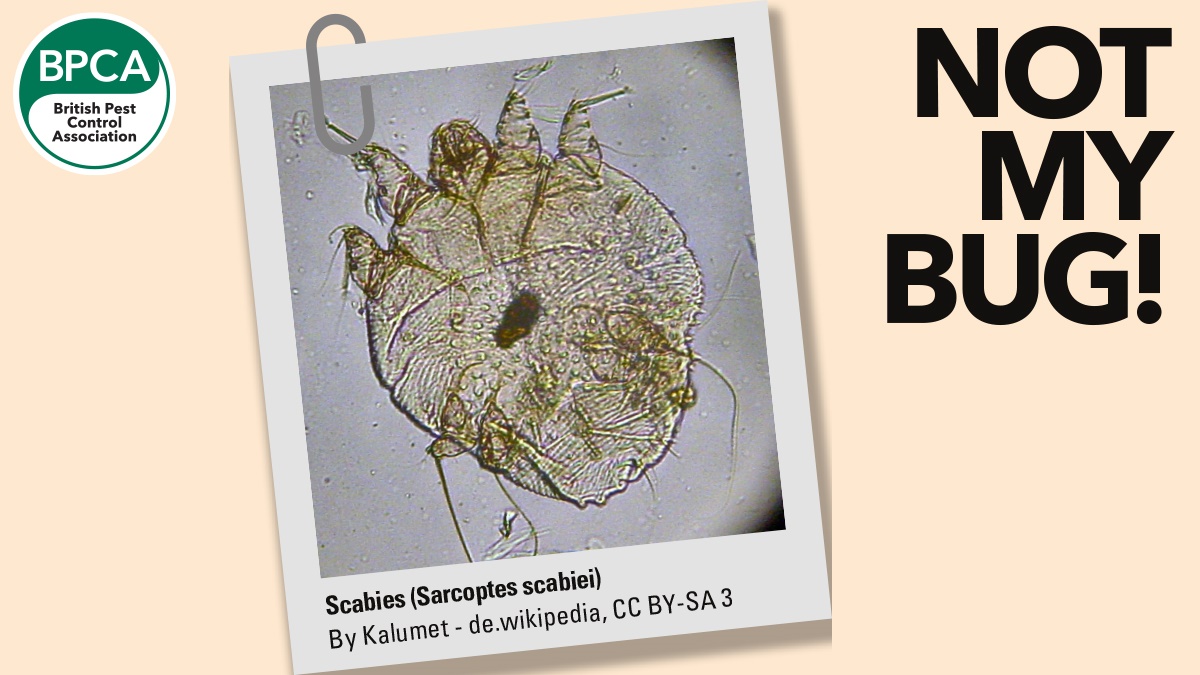

Scabies (Sarcoptes scabiei)

Scabies mites burrow into the skin, causing intense itching and rash.

Identification:

The actual scabies mites are not visible to the naked eye; they require magnification for detection.

However, scabies rash looks like tiny red bumps or blisters, sometimes with visible burrows (tiny tunnels) in the skin where mites have burrowed. The rash can appear anywhere on the body, but is commonly found between fingers, on wrists, elbows, and genitals. In darker skin tones, the redness may be harder to see, but the rash may appear purple or brown.

Of course, as pest professionals we never diagnose skin ailments. You may be fairly certain that it’s scabies, but that diagnosis must come from a medical professional.

Transmission, symptoms and control

Scabies is a highly contagious skin infestation caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis.

These microscopic mites burrow into the upper layer of the skin, causing intense itching and a rash. Classic scabies mites can survive off the human host for 24 to 36 hours.

Scabies spreads rapidly in settings involving close personal contact. Outbreaks are particularly common in shared living environments such as households, long-term care facilities, schools, and child-care centres, where close personal contact increases transmission.

The mites usually infest warm, moist areas of the body, with common sites including skin folds, between fingers and toes, around the waist, and in the groin, often leading to irritation and discomfort.

In infants and young children, scabies may also affect the scalp, neck, palms of the hands, and soles of the feet.

Effective control of scabies requires medical intervention.

Signposting and advice

Pest management professionals cannot treat scabies infestations directly, and individuals suspected of being affected should be referred to a healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment. Prescription topical medications or oral treatments are typically used to eliminate the mites.

In addition to medical treatment, environmental hygiene plays a key role in preventing reinfestation. Bedding, clothing, and towels used by affected individuals should be hot washed−ideally at temperatures above 60°C-and dried thoroughly.

Education is the key

Human-associated arthropods are often unseen yet can spread disease, cause allergies, or be a nuisance. For professionals, education is key−helping clients prevent issues and know when to seek medical help. Vigilance and knowledge remain our best defences.

Lice: Body and Head (Pediculus humanus and Pediculus capitis)

Lice are small, wingless, blood-feeding ectoparasites that infest humans. While body lice (Pediculus humanus) and head lice (Pediculus capitis) appear nearly identical in size and color-typically beige or greyish, with males measuring 2-3 mm and females 3-4 mm - they differ significantly in habitat, behaviour, and health implications.

Identification and habitat

Head lice live directly on the scalp and in the hair, especially around the nape of the neck and behind the ears.

Body lice reside primarily in the seams of clothing, occasionally migrating to the body to feed, and may be found in body hair in severe infestations.

Both types are wingless with inconspicuous eyes and short, five-segmented antennae.

Biology and life cycle

Lice feed exclusively on human blood and are highly dependent on their host. Feeding is enabled by a specialised mouthpart called the haustellum − a flexible, toothed tube used to anchor into skin and draw blood.

Head lice lay 6-8 eggs per day on hair shafts near the scalp. Body lice deposit 6-9 eggs per day on clothing fibers, especially in undergarment seams.

Eggs hatch within 7 to 10 days, and both types go through three nymphal moults before reaching adulthood. Lice typically live 2 to 4 weeks, during which a single female may produce up to 200-300 eggs. Without a blood meal, head lice die in 2-3 days, while body lice may survive up to 10 days post-feeding.

Behaviour and transmission

Head lice infestations are usually limited to 10-20 lice and are spread primarily through close personal contact, especially common in school-aged children. Severe cases may lead to hair matting and secondary infections due to scratching.

Body lice infestations are associated with poor hygiene and crowded living conditions, including homeless shelters, refugee camps, and prisons. They emerge from clothing to bite exposed skin and are more likely than head lice to transmit diseases such as:

- Louse-borne typhus

- Trench fever

- Louse-borne relapsing fever.

Lice are highly sensitive to temperature. Neither species survives well in environments over 40°C, and they often abandon a host shortly after death due to the drop in body heat.

Signposting and advice

While pest professionals cannot treat lice infestations directly, there are several important recommendations:

For Head Lice:

- Use fine-toothed lice combs for daily mechanical removal

- Wash hair with warm water and soap to reduce lice populations

- Over-the-counter chemical treatments are available, but resistance is common−repeated applications and a combined approach are often needed.

For Body Lice:

- Wash infested clothing and bedding at temperatures above 60°C to kill lice and eggs

- Maintain good personal hygiene and replace or clean clothing frequently

- Pharmacists can provide topical treatments, but medical attention is necessary if scratching has led to infection.

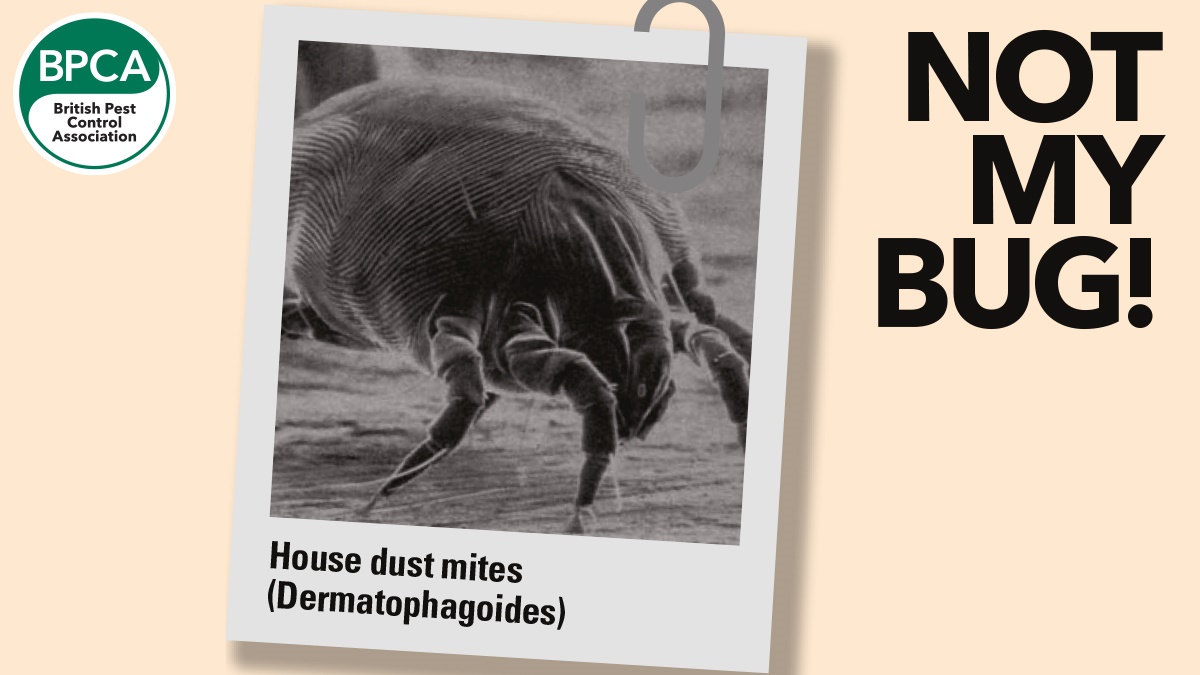

Dust Mites

House dust mites are microscopic arachnids that feed on skin flakes and thrive in humid environments.

Identification: Size: 0.2-0.3 mm, translucent bodies

Biology: Life cycle: 65-100 days; females lay 60-100 eggs in their last five weeks.

Dust mites are prolific microscopic organisms, with a single mite capable of producing up to 20,000 fecal particles over its lifetime. These waste particles, along with their shed skin,

are the primary triggers for allergic reactions in humans.

Though too small to be seen with the naked eye, dust mites play a significant role in indoor air quality and human health.

Despite their microscopic size, dust mites have natural predators. In particular, silverfish and pseudoscorpions are known to feed on them, providing a natural check on their populations in some environments.

However, in most indoor settings, dust mites thrive with little interruption. Dust mites are found around the world, but they flourish in environments with high humidity, poor ventilation, and damp conditions.

Their populations are particularly dense in older mattresses and in lower floor levels of buildings, where moisture tends to accumulate. These factors make certain homes more susceptible to mite infestations, especially in regions with warm, humid climates.

From a health perspective, dust mites are a major source of indoor allergens. They produce a protein called tropomyosin, which is also found in shellfish−explaining the common cross-reactivity between dust mite and shellfish allergies.

In severe cases, ingestion of mite-contaminated food products, such as improperly stored flour, can lead to a rare but serious condition known as oral mite anaphylaxis, or "pancake syndrome.”

Signposting and advice

There are some things you can recommend to someone with an allergy to dust mites, such as reducing the humidity in their home, washing bedding and fabrics regularly, using allergen-proof covers on mattresses or pillows, replacing carpeting with wood or vinyl flooring, and improving ventilation.

You could also signpost them to an allergy specialist. The NHS has allergy specialists, but they would need to get a referral through their GP. There are also many private allergy specialists but these are paid services.

Signposts

Find a GP: nhs.uk/service-search/find-a-gp/

Find a pharmacist: nhs.uk/service-search/pharmacy/find-a-pharmacy

Source: PPC120